The world of reportage drawing encompasses artists who aim for a journalistic objectivity as well as those pursuing a creative agenda in their work. Artist and illustrator Louis Netter of the University of Portsmouth, UK, explores links between reportage and caricature and describes his selection and “stalking” of the subject, to accompany his series of reportage drawings from the streets of Barcelona.

From July 16 to July 18, 2016 I attended The IAFOR International Conference on the City in Barcelona and presented a paper about reportage drawing and the ways in which the act reveals layers of cities’ cultural, social and political composition. The subject of my drawings was Portsmouth in the UK, where I am a senior lecturer in illustration. What I did not anticipate was the rich tableau of subjects that Barcelona had to offer and that engaging with the city through drawing would be so fruitful. During evenings and breaks from the conference I furiously drew and the result was as surprising as those Portsmouth drawings that motivated my paper. To fully understand this experience, some background on reportage drawing, motivations for the act, spaces and places and the visual language of the drawings is essential.

“The nineteenth century saw the prominence of reportage drawing reach new heights with advances in printing and an increasingly interconnected world through trade and war.”

Reportage drawing is the practice of drawing on location or in situ with the intention of capturing some observed subject. This practice is rooted in the desire for information and has historically provided an important function in documenting ritual, places and, most notably, the important events of the time. The nineteenth century saw the prominence of reportage drawing reach new heights with advances in printing and an increasingly interconnected world through trade and war. Reportage artists, who had in previous centuries documented the New World for wealthy clients, business or scientific expedition, were now tasked with documenting daily events, and by the mid-nineteenth century every major Western power had a cadre of domestic and international reportage journalists. International artist correspondents were often the most prized, gaining the moniker “special artist” due to the difficulty of their work documenting war and the dangers it entailed, which often required the artists to carry a gun as well as a pencil while working (Hogarth 1986:30). These drawings were sometimes surreptitiously sketched on cigarette paper to avoid detection, and many of these artists did arouse suspicion from foreign officials as potential spies (Hogarth 1986:30). Because of the print technologies of the day (at least in terms of mass production), much of this work has a homogeneous quality, since original drawings were reproduced and often changed by a wood engraver. Idiosyncratic qualities of original drawings were lost and individual artistic voices flattened by the “house style” of prominent publications. Noted scholar of nineteenth-century printmaking William M. Ivins detailed this flawed process, saying “and finally came the engraver himself, who in many instances had never seen the original of which he was supposed to make a reproduction, and who rarely hesitated to correct what he considered the poor drawing or lack of elegance in the copy that lay before him” (Ivins 1969:97). This was problematic and interfered with the way in which the experience of the artist, as manifest in his or her idiosyncratic visual language, was accessible to the viewer in the copy. Walter Benjamin identified this problem of authenticity during this early age of reproduction, noting, “the authenticity of a thing is the essence of all that is transmissible from its beginning, ranging from its substantive duration to its testimony to the history which it has experienced” (Benjamin 1968:221).

Today the practice is widely varied, with a distinct though porous split between those who still see the act rooted in journalism and therefore objectivity and those who see it as a means to extend creative agendas. Of course there is considerable overlap between the two positions, and even creative approaches to the act maintain a crucial anchorage to the observed subject and the circumstances on the ground in situ. What connects all reportage practitioners is the value of drawing on location and the way in which the in situ environment and the simultaneity of the act fuses the concerns of the artist and makes choices in subject matter and approach unified, resulting in work that is both evocative and surprising.

The reportage drawing that I engage in requires walking in cities and looking with a specific intent to find subjects. Ian Sinclair, one of the many writers carrying forward the psychogeographers’ mantle, claimed that walking was now “with a thesis” and “with a prey” (Coverly 2010:120). This kind of walking is done with a sentient eye, looking for those subjects that both confirm an existing worldview and fit within an established creative oeuvre, or are anomalistic and challenge those preconceptions. Although considered a break from the Flâneur and subsequent movements, Sinclair acknowledges that this premeditated approach has a significant duality in that it “knows where it is going (or seeking) but not why or how” (Coverly 2010:120). The courting of the unexpected occurs in both practices and the resulting kaleidoscopic quality of a body of drawings done on location speaks to this methodology that is at once focused and moveable, open to circumstances on the ground.

Significant to how drawings reveal aspects of the city, condensing impressionistic and purposive observations, is the transformation of place to space. Within this transformation is our experience of said place and how we internalise it. Yi Fu Tuan, in his book Space and Place, notes that “an object or place achieves concrete reality when our experience of it is total, that is, through all the senses as well as with the active and reflective mind” (Tuan 1977:18). Drawings can be said to concretise this experience, and, through the filter of drawing and complex intentions, render not just an observed moment stolen from reality but also the totality of thoughts, emotions and creative intentions that unfolds throughout the drawing process. Because the act is demanding of all of the artist’s faculties and necessitates rapid, responsive drawing, the revelation of these layers of experience occurs only when the drawing is finished. Although the subject of the drawing is important, so too is the pause in movement that the drawing represents. The subject is a selection but the artist must stop to be able to draw, and this pause, as noted by Yi Fu Tuan, “makes it possible for a locality to become a centre of felt value” (Tuan 1977:138). The drawing affixes value to the observed moment and this is as much a revelation of the subject (and by extension the space or place) as it is the artist’s intentions.

“What is significant about the link between reportage drawing and caricature is the way in which both rely on an understanding of the subject in order to be capable of distorting it.”

While the above is essential to understanding the origins of the act and the procedural considerations of the reportage drawing experience, the drawings themselves, as the containers of this experience, offer much to decode. Because the drawings are often produced quickly and under less than ideal circumstances, they exhibit, as Gombrich notes of all artworks, “pardonable abbreviation”, and are works created within the tension between the artistic desire to render a motif and their own limitations (ability, circumstances, and so on) (Gombrich 1972:65). This inevitably leads to a greater economy in the artwork and the much-sought rawness of vision that artists value for purging their work of conventions. Reportage drawing is often seen as collectively sharing a quality of gesture and abbreviation that reflects the circumstances of its making. What also emerges is artistic intent, and the responsive line, on top of notational observations, is rendering commentary in the form of amplified distortions. These stylistic decisions often dip into caricature as the reductive line takes on symbolic significance and subjects are rendered in a single “salient characteristic” (Gombrich 1938:322). What is also significant about the link between reportage drawing and caricature is the way in which both rely on an understanding of the subject in order to be capable of distorting it. While reportage drawing occurs quickly and often without premeditation, the application of the drawing pulls on prior (and often extensive) experience and drawing that provides a large vocabulary of schematic approaches to form from which to apply. The visual language of the reportage artist, like that of a caricaturist, relies on an approach to rendering form that is informed by both observation and a more conscious inclination toward comment. However, reportage artists who see their work as rooted in observation and even journalistic concerns of objectivity deny implicit commentary and further, disavow any connection to intentions beyond representation.

The distortions noted above, which feature quite heavily in my own work, do relate to and reflect the features of the grotesque. Because reportage often seeks human subjects and, as mentioned above, through hurried drawing and artistic intention, leads to distortion, the carnivalesque tradition that marks the grotesque is clearly evident (Connelly 2014:92). The function of the grotesque in reportage drawing is particularly appropriate in that it necessarily deals in the duality between the observed or observable and the drawn, which arguably can only ever be an approximation of the observed. This relates to aspects of the uncanny that plays on the “bodily form” and the “conceptual form” that, in the case of reportage, relates to the recognisable forms in the drawing and ways in which those forms bend with the intentions of the artist (Edwards 2013:6). The extent to which these distortions and the way they are perceived is more or less playing (and preying) upon ideas of the grotesque is down to the individual artist. Because the grotesque functions in part through amplified distinctions between the “normal” and “abnormal”, the drawings are often evocative of their subjects and therefore, when the subject is a specific location, becomes a record of highly subjective experience and commentary (Edwards 2013:9). The prominence of the grotesque in the modern era is in part due to what Frances Connelly says is “its hybrid, ambivalent, and changeful character” and that the grotesque has been the “quintessential voice of the outsider” bringing “both comic relief and a sense of empathy in a cybernetic age” (Connelly 2014:22-23). This is an important outgrowth of reportage drawing and a way in which the act brings a new lens to the ever complex and absurd society we live in.

“Much of the success or failure of a drawing is in the delicate balance between observation and comment.”

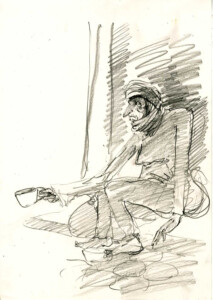

The drawings I produced in Barcelona, included here, speak to the ways in which visual language becomes, in the act of reportage, a fusion of observation and comment and, as above, “bodily forms” and “conceptual forms”. The subjects were chosen because they presented to me some compelling property that was both consciously attached to the place and seemed universally relevant, pointing to wider social issues. Some subjects are chosen because they are simply emblematic of the place, and many of the included drawings here fit that description. What happens in the “stalking” of the subject is a two-fold desire for an evocative subject and a successful drawing. Typically, the chosen drawings fit both criteria, and their expressive force is such because it lends itself to drawing or, at least, to my own approach. In the stalking there is some pre-thought as to how the subject can be rendered and what my overarching concern is for the work. For some included here, it is the expressive gesture and some accentuation of an observed absurdity. For others, it is a strong shape or a contrast. Overriding all concerns is a desire to say something in the drawing, and this desire, although explicit, does not find certainty until the drawing is complete. Much of the success or failure of a drawing is in the delicate balance between observation and comment, and in the even thinner line between stylistic departure and anchorage to the original subject. When the commentary loosens its grip on the observed subject and departs into generalisation, the drawing is a schematic exercise and does not capture an experience on the ground. Whether an outsider can perceive this difference is another story, although there is a perceptible drift if one is attuned to the workings of the artist.

When we are left just to look at the drawings, much more comes to the fore and we connect with similar experiences to those depicted and our own developed understanding of drawing and visual languages. As Michel de Certeau notes, “art is a kind of knowledge essential in itself but unreadable without science. This is a dangerous position for science to be in because it retains only the power of expressing the knowledge which it lacks.” (Certeau 2008:68)

The “truth” in the work is a complex summation of the total experience of the reportage artist and the perception, by the artist and/or the viewer, of the successful preservation of said experience in drawing. Depending on the orientation of the artist, this truth could be on either side of the objective and subjective scale and be laden with varied expectations. Ultimately, this can be identified as a successful communion with the experience of the artist and a tangible connection to both an observed subject and an artist operating within his or her artistic and observational capacities.

Reportage Drawing in Barcelona by Louis Netter

All images Copyright © Louis Netter 2016. All rights reserved.

References

Benjamin, W., Arendt, H., & Zohn, H. (1968). Illuminations. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World.

Certeau, M. D. (2008). The practice of everyday life. Berkeley, California: University of California Press.

Connelly, F. S. (2014). The grotesque in Western art and culture: The image at play. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Coverley, M. (2010). Psychogeography. Harpenden: Pocket Essentials.

Edwards, J. D., & Graulund, R. (2013). Grotesque. Abingdon: Routledge.

Gombrich, E. H. (1938), The principles of caricature. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 17:3-4 (Trapp no.1938a.1), pp. 319-42.

Gombrich, E. H. (1972). Art and illusion: A study in the psychology of pictorial representation. Nat. Gallery of Art, Washington, 1956. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Hogarth, P. (1986). The artist as reporter. London: Gordon Fraser.

Ivins, W. M. (1969). Prints and visual communication. New York: Da Capo Press.

Tuan, Y. (1977). Space and place: The perspective of experience. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Related

Join the conversation! 2 Comments

Comments are closed.

[…] Netter, L. (2019a). Reportage Drawing, Visual Language and Discovery. [online] THINK.IAFOR.ORG. Available at: https://think.iafor.org/serendipitous-city-reportage-drawing-visual-language-discovery/. […]

[…] SERENDIPITOUS CITY: REPORTAGE DRAWING, VISUAL LANGUAGE AND DISCOVER. Available at: https://think.iafor.org/serendipitous-city-reportage-drawing-visual-language-discovery/ (Accessed: 12 November […]